Background

I write what I call Heritage Fiction—novels about my ancestors. My interests lie in history, genealogy, and finding the truth. Although I write fiction, I use as many facts as I can to formulate my stories. The first novel I published, The Pulse of His Soul, was about Reverend John Lothropp (1584-1653), an Anglican minister in England during a tumultuous period when citizens of the kingdom were forced to attend the Church of England and no other. It was a time when people risked prison, torture, and death by defying the Church’s rigid laws about attendance and religious beliefs. One step out of line might find a person branded a heretic, causing arrest and prosecution before the dreaded Star Chamber at the royal Palace of Westminster. This is what happened to Reverend Lothropp, who came up against the formidable Archbishop William Laud.

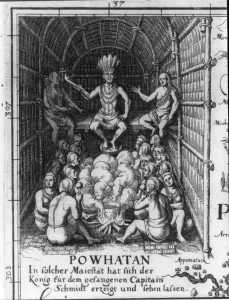

With this background of research in 17th century Britain, I have written a three-book series about another Englishman of the same period. Thomas Savage sailed to the New World in 1608 when he was thirteen on the first supply ship bringing much needed food and supplies to British settlers in Jamestown. Savage had been in Virginia only two weeks before Captains John Smith and Christopher Newport traded him to the Native American Pamunkey Tribe to learn their language and culture. Savage became an accomplished interpreter for Jamestown and Powhatan leaders. He lived with the mamanatowick (emperor) Chief Powhatan for over two and a half years, becoming friends with Pocahontas.

For the third book in the Jamestown series, I have researched Pocahontas’s visit to England (1616-1617) and subsequently investigated the writings of Reverend Samuel Purchas, who interviewed the Powhatan Priest Tomocomo who had traveled to England with Pocahontas. Reverend Purchas found an interest in the religion of the Eastern Woodland Indians (also known as Powhatans). The Powhatans are sometimes referred to as Algonquians because of the Algonquian language they spoke and their common culture with tribes along the Eastern coast as far north as present-day Canada, east of the Rocky Mountains.

It appears Priest Tomocomo knew only some of the English language and had present for the interview the interpreter Thomas Savage, who Purchas refers to as “Dale’s interpreter.” Sir Thomas Dale had been the acting governor of Jamestown (March 1614 to April 1616) and came to England with Pocahontas’s group. He was the commander over Thomas Savage, who it appears served an indentured period for the Jamestown leaders from 1610-1617, after his years with the Pamunkeys. But Sir Dale was not present when Reverend Purchas interviewed Priest Tomocomo. Pocahontas was not present either, but her English husband John Rolfe was. The interview was held in the home of Doctor Theodore Goldstone, who lived near the Belle Savage Inn where Pocahontas and her group resided many months in London. I am not aware if there were others present at the interview.

The Powhatans did not have a written language when the Europeans settled on their lands in the early 1600s. Subsequently, records of the Jamestown Settlement were biased toward the British experience, religion, and peoples. Even if self-pride or imperialism was not recognized, an Englishman knew not to champion a common spiritual practice between the Church of England and Powhatan religion. He would be foolish to voice Powhatan religious leanings or questions because it would be considered heretical and he could be horribly punished with the threats of imprisonment, torture, or death (as John Lothropp was).

No one knows how much indoctrination took place for those who grew up in Britain during this time of Protestant Reformation. From what I have read, it appears an Englishperson would stand by his religion to the point of ignorantly referring to the Native Americans as “savages” and “heathens” because they did not believe as the Anglicans did. This was not a time of freedom of religion or speech. Quite the opposite.

Wanting to be fair-minded with my Jamestown stories (partially because in the end Thomas Savage chose to live the rest of his life with the Native Americans), I also read contemporary anthropological research about the Powhatan culture, trying to determine what was fact and fiction. Not an easy task, to be sure. Some academics could only guess at what the Powhatans truly believed when it came to their one supreme god, Ahone, or their devil god (as the English called him) Okeeus. (Alternate spellings: Okeus, Okee, Oke, Oki.)

Okeeus is a confusing fellow. The Powhatans (according to the English!) believed Okeeus could bring a drought, cause crop failures, disease, death, and basically anything bad. He is associated with war. The Powhatan priests would try to intercede by appeasing Okeeus with supplications of prayers and offerings of tobacco, deer suet, blood, precious beads, and other valuables. Some of these offerings were made on altar stones. Not appeasing Okeeus invited punishment.

But then there’s the other beliefs about Okeeus to whom temples were dedicated. He kept a close watch on the doings of men and could be found in the air, thunder, and storms.

The priests who served Chief Powhatan were considered wise and a conduit to a greater being who gave direction through ambiguous conversation, dreams, or deceased ancestors. Chief Powhatan would not go against what his priest told him to do in any given matter.

To the Point – The Interview

Below is part of the original interview between Reverend Samuel Purchas and the Powhatan Priest Tomocomo.

Of their [Powhatans] opinions and ceremonies in religion, who fitter to be heard than a Virginian?—an experienced man and counselor to Opochancanough [sp], their king and governor in Powhatan’s absence. Such is Tomocomo, at this present in England, sent hither to observe and bring news of our king and country to his nation. Some others which have been here in former times being more silly, which having seen little else than this city, have reported much of the houses and men, but thought we had small store of corn or trees, the Virginians imagining that our men came into their country for supply of these defects. This man [Tomocomo], therefore, being landed in the west parts, found cause of admiration at our plenty in these kinds, and, as some have reported, began to tell [tally?] both men and trees till his arithmetic failed. For their numb’ring beyond an hundred is imperfect and somewhat confused. Of him (Sir Thomas Dale’s man being our interpreter) I learned that their Okeeus doth often appear to them in his house or temple. The manner of which apparition is thus:

First, four of their priests, or sacred persons, of which he [Tomocomo] said he was one, go into the house, and by certain words of a strange language—which he repeated very roundly in my hearing, but the interpreter understood not a word, nor do the common people—call or conjure this Okeeus, who appeareth to them out of the air; thence coming into the house, and walking up and down with strange words and gestures, causeth eight more of the principal persons to be called in; all which twelve standing round about him, he prescribes to them what he would have done.

Of him they depend in all their proceedings, if it be but in a hunting journey, who by winds or other awful tokens of his presence holds them in a superstitious both fear and confidence. His apparition is in form of a personable Virginian, with a long black lock on the left side hanging down near to the foot…this Virginian so admiring this rite, that in arguing about religion he [Tomocomo] objected to our god this defect that he [God] had not taught us so to wear our hair. After that he [Okeus?] hath stayed with his twelve so long as he thinks fit, he departeth up into the air whence he came. Tomocomo averred that this was he which made heaven and earth; had taught them to plant so many kinds of corn; was the author of their good; had prophesied to them [Powhatans?] before of our men’s [the English] coming; knew all our country; whom he made acquainted [known to Tomocomo?] with his coming hither [to England?], and told him that within so many months he would return. But the devil, or Okeeus, answered that it would be so many more. Neither at his return must he go into that house [temple] till Okeeus shall call him. He [Tomocomo] is very zealous in his superstition and will hear no persuasions to the truth, bidding us teach the boys and girls which were brought over from thence [children in Pocahontas’s retinue], he being too old now to learn. Being asked what became of the souls of dead men, he [Tomocomo] pointed up to heaven; but of wicked men that they hung between heaven and earth.

~As recorded in Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony, The First Decade 1607-1617, compiled and edited by Edward Wright Haile, pp 880-884. Haile’s references Purchas His Pilgrimage or Relations of the World 1617:954, 1626:844, and Hakluytus Posthumus or, Purchas His Pilgrims 1625:1774 (Vol 19, pp 118-119).

Breaking it Down

How much did Reverend Purchas understand of what Priest Tomocomo said? Was he writing as Priest Tomocomo spoke, or did he write it down that evening after everyone left, or at some other time? Because that could make a difference. Did Reverend Purchas assume Priest Tomocomo was speaking about Okeeus when he wasn’t?

Perhaps more importantly, was it a coincidence that Priest Tomocomo spoke of the “he” who left his twelve by departing up in the air wence he came (which seems to mean he descended in like manner), then listed the other attributes of this “he” as:

This was he which made heaven and earth

Had taught them to plant so many kinds of corn [crops?]

Was the author of their good

Had prophesied to them before of our men’s [the English] coming

Knew all our country [England]

Whom he made acquainted with his coming hither [He will return?]

And told him that within so many months he would return. But the devil, or Okeeus, answered that it would be so many more. Neither at his return must he go into that house [temple?] till Okeeus shall call him.

If I’m following, someone will be returning and not allowed in the house or temple until Okeeus calls him.

Does Reverend Purchas interchange Okeeus and Ahone?

It seems suspect that Priest Tomocomo has a story about a man leaving his twelve and ascending into the air. And that same man is the one who has attributes like Christ.

In the sentence After that he [Okeus?] hath stayed with his twelve so long as he thinks fit, he departeth up into the air whence he came, the “After that he…” looks to have been tacked on to a paragraph that it doesn’t belong to. So, I asked myself, “after what?” There appears to be something missing here. I am certain Reverend Purchas does not follow the English rule of grammar that a pronoun following a proper name refers back to the last proper name given. For this reason, his writing is confusing. A few commas would have helped too!

Did the Powhatans have Jewish or Christian ancestors to have knowledge about the history of Christ, but the devil corrupted it, selling himself as the man (Christ) who had come to them earlier? We’ve heard it said that the devil is the great pretender. And although the Purchas interview is perhaps hard to understand and sometimes confusing, I think there’s enough there to try and figure it out.

If Priest Tomocomo was speaking of Christ, why did he not refer to him as the son of God or of some kind of relation to God/Ahone? From what I’ve read, the relationship between Ahone and Okeeus was never made clear, or the British didn’t think to write it down.

It appears Priest Tomocomo had a sacred language used in prayers in the Powhatan temple, which he recited for the group present. Even the interpreter Thomas Savage, who was fluent in Powhatan, did not understand what he said.

When Priest Tomocomo speaks of the twelve and the “man” who left by disappearing into the air, why does not anyone in the room, all being Anglican, see a correlation to the Ascension of Christ? Would they consider it sacrilege or heretical to broach that subject? I think so, considering the religious dogma of the time.

Or was Priest Tomocomo saying that in their temple, they (priests, him included) gathered with four and then eight other priests joining them, making twelve. Were they reenacting something honorable or wicked? And what was the root of that reenactment?

Being asked what became of the souls of dead men, Priest Tomocomo pointed up to heaven, showing that the Powhatans had a belief in a “heaven” above. But of wicked men, the Powhatans believed they “hung between heaven and earth,” which sounds very much like a spirit prison.

Reverend Purchas challenged Priest Tomocomo to abandon his beliefs and become Christian as Pocahontas had. Priest Tomocomo answered that he was too old to do that, but they (Reverend Purchas and others) were welcome to teach the children who had come to England with Pocahontas. No one is sure who these children were, but I suspect they were Native children who had been captured years before when English soldiers raided and plundered villages, killing the Native peoples of Virginia. These children were placed with Reverend Whitaker (the same man who helped in Pocahontas’s conversion to Christianity after her kidnapping) in Rocke Hall in Henricus, a town upriver from Jamestown, now known as Farrar’s Island. The children were taught not just Christianity but also the English language and academic subjects. Sir Dale had hoped to one day open a university for them and others, but a second war with the Powhatans foiled his plans.

The interview between Reverend Purchas and Priest Tomocomo is not printed in entirety here. Priest Tomocomo had also explained the huskanaw ceremony for teenage boys and more about the hair style of Powhatan men. He had also said the Powhatans “hold it a disgrace to fear death, and therefore when they must die do it resolutely.”

Additional Information of Interest

As a practice, the Powhatans took on a new name when something of great meaning changed their life course, or perhaps for other reasons unknown. Sometimes this new name was kept secret among the tribe members because if their enemies discovered the new name, their life could be at risk. There are dozens of examples, but to name a couple: when Pocahontas became a woman, she took on the secret name Matoaka, and when she was baptized Christian, she became Rebecca and could then share the name Matoaka because it was no longer secret or meaningful. Priest Tomocomo was known as Uttamatomakin before he made the great voyage to England at the request of his paramount chief.

Other common values and beliefs of the Powhatan, Jew, and Christian:

- marriage between a husband and a wife (although chiefs could have multiple wives)

- laws, courts, and punishments for such crimes as murder, adultery, and theft

- fasting when praying for a need

- giving sacrifice at meals, offering part of the first fruits or animals to their god and then to their ruler before partaking themselves

- praying at mealtimes

- believing in an afterlife and heavenly place to live

- had temples which the English knew little about because of the holiness of the building

- had a strong belief in their deceased ancestors guiding their lives, inviting them into their prayer circles.

Unlike the English, for the most part, the Powhatans allowed others to have their own religious beliefs. They did not have an organized church. Not all tribes agreed on the creation story, but they all did have a creation story and were very interested in the Christian creation story. John Rolfe wrote that the Natives were inconsistent in stating religious beliefs, “one denying that which another affirmeth.” One chief had asked the English to pray for rain because his gods would not send him any.

How much did the Natives and English Settlers have in common? How did the English misunderstand—and have we misunderstood—those people who were already here when the Anglicans established the Virginia Colony? We may never completely know. If only the Powhatans had left a written record.