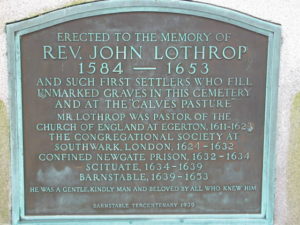

Rev. John Lothropp (1584–1653) — sometimes spelled Lothrop or Lathrop — was an English Anglican clergyman, who became a Congregationalist minister and emigrant to New England. He was among the first settl ers of Barnstable, Massachusetts. Perhaps Lothropp’s principal claim to fame is that he was a strong proponent of the idea of the Separation of Church and State (also called “Freedom of Religion”). This idea was considered heretical in England during his time, but eventually became the mainstream view of people in the United States of America, because of the efforts of John Lothropp and others. Lothropp left an indelible mark on the culture of New England, and through that, upon the rest of the country. He has had many notable descendants, including at least six US presidents, as well as many other prominent Governors, government leaders, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and business people.

ers of Barnstable, Massachusetts. Perhaps Lothropp’s principal claim to fame is that he was a strong proponent of the idea of the Separation of Church and State (also called “Freedom of Religion”). This idea was considered heretical in England during his time, but eventually became the mainstream view of people in the United States of America, because of the efforts of John Lothropp and others. Lothropp left an indelible mark on the culture of New England, and through that, upon the rest of the country. He has had many notable descendants, including at least six US presidents, as well as many other prominent Governors, government leaders, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and business people.

Early life

Lothropp was born in Etton, East Riding of Yorkshire. He was baptised on 20 December 1584. He attended Queens’ College, Cambridge, where he matriculated in 1601, graduated with a BA in 1605, and with an MA in 1609.[1]

Ministry and incarceration

He was ordained in the Church of England and appointed curate of a local parish in Egerton, Kent. In 1623 he renounced his orders and joined the cause of the Independents. Lothropp gained prominence in 1624, when he was called to replace Reverend Henry Jacob as the pastor of the First Independent Church in London, a congregation of sixty members which met at Southwark. Church historians sometimes call this church the Jacob-Lathrop-Jessey (JLJ[2]) Church, named for its first three pastors, Henry Jacob, John Lothropp and Henry Jessey.

They were forced to meet in private to avoid the scrutiny of Bishop of London William Laud. Following the group’s discovery on 22 April 1632 by officers of the king, forty-two of Lothropp’s Independents were arrested. Only eighteen  escaped capture. The arrested were prosecuted for failure to take the oath of loyalty to the established church. Evidence gleaned by the historians Burrage and Kiffin and from the Jessey records indicate many were jailed in The Clink prison. As for Reverend John Lothropp, the question is still unresolved. English historian Samuel Rawson Gardiner, whose book Reports of Cases in the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission, gives an account of the courtroom trial and cites information from the trial record that the convicted dissenters were to be divided up and sent to various prisons. Historian E. B. Huntington suggests Lothropp was incarcerated in either the Clink or Newgate.[3] Further, it may be that Lothropp actually served time in both prisons since it was customary to move prisoners from one prison to another due to space availability. In the end, the precise location of Lothropp’s imprisonment is not confirmable from primary documentation.

escaped capture. The arrested were prosecuted for failure to take the oath of loyalty to the established church. Evidence gleaned by the historians Burrage and Kiffin and from the Jessey records indicate many were jailed in The Clink prison. As for Reverend John Lothropp, the question is still unresolved. English historian Samuel Rawson Gardiner, whose book Reports of Cases in the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission, gives an account of the courtroom trial and cites information from the trial record that the convicted dissenters were to be divided up and sent to various prisons. Historian E. B. Huntington suggests Lothropp was incarcerated in either the Clink or Newgate.[3] Further, it may be that Lothropp actually served time in both prisons since it was customary to move prisoners from one prison to another due to space availability. In the end, the precise location of Lothropp’s imprisonment is not confirmable from primary documentation.

While Lothropp was in prison, his wife Hannah House became ill and died. His six surviving children were, according to tradition, left to fend for themselves begging for bread on the streets of London. Friends, being unable to care for his children, brought them to the Bishop who had charge of Lothropp. After about a year, all were released on bail except Lothropp, who was deemed too dangerous to be set at liberty. The Bishop ultimately released him on bond in May 1634 with the understanding that he would immediately remove to the New World. Since he did not immediately leave for the New World, a court order was subsequently put out for him. Family tradition and other historical reflections indicate he then “escaped.”

Emigration

Lothropp was told that he would be pardoned upon acceptance of terms to leave England permanently with his family along with as many of his congregation members as he could take who would not accept the authority of the Church of England. Lathrop accepted the terms of the offer and left for Plymouth, Massachusetts. With his group, he sailed on the Griffin and arrived in Boston on 18 September 1634.[4] The record found on page 71 of Governor Winthrop’s Journal, quotes John Lothropp, a freeman, rejoicing in finding a “church without a bishop. . .and a state without a king.” John Lothropp married Ann (surname unknown) (1616–1687).[5]

Lothropp did not stay in Boston long. Within days, he and his group relocated to Scituate where they “joined in covenaunt together” along with nine others who preceded them to form the “church of Christ collected att Scituate.”[6] The Congregation at Scituate was not a success. Dissent on the issue of baptism as well as other unspecified grievances and the lack of good grazing land and fodder for their cattle caused the church in Scituate to split in 1638.

Lothropp petitioned Governor Thomas Prence in Plymouth for a “place for the transplanting of us, to the end that God  might have more glory and wee more comfort.”[7] Thus as Otis says “Mr. Lothropp and a large company arrived in Barnstable, 11 October 1639 O.S., bringing with them the crops which they had raised in Scituate.”[8] There, within three years they had built homes for all the families and then Lothropp began construction on a larger, sturdier meeting house adjacent to Coggin’s (or Cooper’s) Pond, which was completed in 1644. This building, now part of the Sturgis Library in Barnstable, Massachusetts is one of John Lothrop’s original homes and meeting houses, and is now also the oldest building housing a public library in the USA.

might have more glory and wee more comfort.”[7] Thus as Otis says “Mr. Lothropp and a large company arrived in Barnstable, 11 October 1639 O.S., bringing with them the crops which they had raised in Scituate.”[8] There, within three years they had built homes for all the families and then Lothropp began construction on a larger, sturdier meeting house adjacent to Coggin’s (or Cooper’s) Pond, which was completed in 1644. This building, now part of the Sturgis Library in Barnstable, Massachusetts is one of John Lothrop’s original homes and meeting houses, and is now also the oldest building housing a public library in the USA.